Bison Skull

Complete bison skull still in place with rest of bone bed.

|

Tedious Work

Sam Drucker (BLM), Anna Yoder (BLM-Lander) and Jennifer Ralston (CAR) uncovering bones in June 2005.

|

Missing Skull

Erosion damage as seen in May 2005 with a partially exposed bison skull that was stolen a few weeks after this picture was taken.

|

Screening

Tony Plastino (CAR) screens a bucket of dirt looking for small artifacts. All dirt is run through a screen and any bone fragment or artifact more than 1/4 inch is put in the screen bag for later analysis.

|

Screening Fun

Volunteers Cleve Bell (from Lander) and Jessie Cox (from Lander) are enjoying screening dirt and finding bone fragments.

|

Arrowhead

Complete chert arrow point. One of 28 points found at Wardell this year.

|

Wrapping Bones

Mike Frankus (CAR) documents bones while Karen Rogers carefully removes and wraps them in aluminum foil.

|

Frison and Reher

Sam Drucker (BLM), Dave Vlcek (BLM), Charles Reher and George Frison visited the site in the fall of 2004 to formulate a stabilization plan. Reher and Frison were the principle excavators in 1970.

|

Articulated Vertebrae

Articulated spinal column indicates bones were deposited here while soft tissues were still attached.

|

Plaster Casting

Plaster cast over a bison skull. Fragile bones are cast in plaster prior to removal to keep them intact for later analysis.

|

Paperwork

Dave Vlcek (BLM) and Kathy Gunderman (BLM) document a bone bed while - left to right – Bonnie Grey (BLM), Oakley Ingersol (BLM) and Ben Weber (CAR) watch. Every bone is numbered and mapped prior to removal.

|

Box of Bones

Box of bones for one layer of one square meter segment of the grid. Each fragment is bagged for later analysis.

|

Big and Little Points

Large Avonlea point (about 1-1/2 inches) and very small obsidian point (less than 1/2 inch) both found in 2005.

|

Archy Tools

Brush, trowel, bamboo stick, and plastic bags are the tools of the trade at an archaeological excavation.

|

|

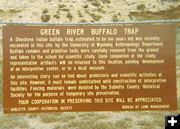

Wardell Buffalo Trap Revisited

BLM Archaeologists revisit prehistoric Indian buffalo kill site

by Clint Gilchrist & Dawn Ballou

September 10, 2005

‘Organized chaos’ may be the best way to describe a group of Indians on foot driving a herd of 1500-pound wild bison at full speed for as much as a mile into a specially built corral of juniper and sagebrush and then killing them with bow and arrows. It would have taken a long time for full-grown, excited, angry bison to bleed to death from the small 1-2” stone arrowheads, giving them plenty of time to raise havoc.

It seems inevitable that people would get injured or killed during the drive or kill. But the danger was acceptable because the success of the fall hunt could be the difference between life and death for the whole group in the upcoming harsh Rocky Mountain winter. One thousand years ago, right here in our Upper Green River Valley, this very scene unfolded over and over again each fall not far from Big Piney.

THEN AND NOW

We know this hunting event actually happened because of a very special place known as the Wardell Buffalo Trap archaeological site. In sharp contrast to those dramatic ancient events, this past summer a group of dedicated archaeologists from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and numerous volunteers, quietly spent three months meticulously removing soil with small brooms and trowels to uncover the preserved bones of those ancient bison. The only dangers now are mosquitoes, horseflies, scorpions and the rays of the hot sun. The modern crew seems just as driven and intent on trying to understand what happened here 1000 years ago as the original hunters probably were at their mission.

Most people have heard of “buffalo jumps”. With this method, people drove stampeding buffalo to their deaths by running them over high cliffs. This was a relatively effective method of resolving the problem of how to kill buffalo to get a supply of winter meat. However, the scene that took place near Big Piney was not a jump, but rather a “buffalo trap”, where the animals were herded into a confined pen and then killed.

The Wardell site was originally excavated in 1970 by Wyoming archaeology legend, Dr. George C. Frison. The site is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, but knowledge of it has been kept very low profile to reduce the chance of vandalism and theft of artifacts. The locals knew about it, but for the most part, the site location is kept off maps and people purposely did not draw attention to it.

The Wardell Buffalo Trap has become almost legendary in professional circles for its contribution to the knowledge of late prehistoric human buffalo procurement. It is the earliest known evidence of a communal bison kill involving use of bow and arrow in the northwest plains.

THE 2005 DIG

Years of ongoing erosion, and looting in the spring of 2005, threatened the Wardell archaeology site and prompted the BLM to take steps to stabilize and protect it. The site is regularly monitored, and this spring archaeologists discovered someone had dug out a number of bison bones, skulls, and unknown artifacts. The BLM decided a new dig was needed to extract vulnerable bones and artifacts before the site was stabilized.

BLM Archaeologist/Paleontology Coordinator, Sam Drucker, led the team for the 2005 Wardell excavation. The BLM archaeology crew was already extremely busy due to the tremendous workload from Pinedale Anticline and Jonah Field oil and gas projects. The crew originally wasn’t given much time, just one week to recover as much as they could. Due to the large volume of threatened artifacts and bones, the original plan for just one week of excavations this summer stretched to three months, much to the delight of the archaeologists.

The crew excavated an 18 square meter area to an average depth of 2 meters, south of the 1970 dig area. Some areas were 3 meters deep in bone and the crew estimates they collected ¾ of a ton of bison bones. In addition, they found 28 projectile points, 1 drill, several bifaces, fire cracked rock and groundstone. A wide variety of bison bones were found, including several complete skulls and two clear instances of articulated vertebrae and legs, indicating those bones were found where they were originally deposited. Other species were also discovered within the bone layer. These may include dogs and bears as well as antelope.

Drucker speculates that the location they excavated was an old arroyo that the prehistoric people filled with discarded bison parts, essentially a garbage pit. “That’s what most archaeologists dig in,” joked Drucker. There appear to be two layers. One has burnt wood and bone on top suggesting it was intentionally fired maybe to kill the stench. The lower layer contains thousands of fly/maggot casings just below another thin layer of burning.

The bones they found could represent more than 30 individual bison, which varied widely in age. The archaeologists recovered fetal and calf remains, which are important to establishing the time of year the site was used. A good collection of carbon (burnt wood) was obtained which should aid in further refining the time period of the site.

Based on their data from the 1970 dig, researchers speculate that a group of 100-125 individuals built a 50 by 30 foot corral of juniper and cottonwood at the base of a bluff about one mile from the Green River. They possibly built drivelines of trees and sagebrush in a V shape ¼ to ½ mile stretching out from the trap. Small herds of maybe 20 bison were diverted on their way back from getting water. It was extremely dangerous and took intimate knowledge of the buffalo. It required extensive advance planning and then a coordinated effort during the drive and kill.

Cultural affiliation of the hunters cannot be precisely determined, but some projectile points and pottery suggest they may have been Athabascan migrating out of the Canadian Rockies. It is unlikely these early people were Crow, Shoshonean or southwestern origin. It is also not clear if the population lived permanently in the valley. Indications of long period use of the site, and projectile points made of local chert stock, suggest a good knowledge of the area. Obsidian found originates in the Yellowstone Park area.

AN INCREDIBLE TEAM OF VOLUNTEERS

In an effort to get as much done in the short time allotted, a quiet call for help was made to the Wyoming Association of Professional Archeologists (WAPA). That call resulted in 29 eager volunteers rallying to help the cause. Publicity about the ongoing dig was purposely kept to a minimum.

Most noteworthy of the volunteers was Bill Current, of Current Archeological Research (CAR), who works out of Rock Springs. He was not able to come out to the dig site himself, but reassigned some of his employees throughout the summer to come and dig, donating hundreds of hours.

In addition to the many volunteers, 29 BLM personnel from the Lander, Kemmerer, and Pinedale field offices found hundreds of hours a few at a time to contribute to the archaeological excavation effort. The two constants throughout the summer were Drucker and BLM GIS Specialist Karen Rogers. Both were recently given awards by the BLM for their work on the 2005 Wardell dig.

When asked about the decision to commit people resources at a time when everyone is so busy, BLM Field Manager Prill Mecham called the site, “one of the most significant sites in the country that was threatened by erosion and looting and was important to preserve”. She added, “The site has a high potential for information and needed to be stabilized.”

Pinedale BLM Archaeologist, Dave Vlcek said, “In the 34 years of cultural resource surveys in the area since the original dig, there has never been a site as rich in volume and preservation for the time period of use.” He added, “It is one of only two known communal bison kill sites in western Wyoming, and the only one excavated”. The findings from Wardell are still almost universally cited in works of late prehistoric research in the Northern Plains.

FURTHERING THE KNOWLEDGE BASE

It is clear that working on this site was something special. Sam Drucker said, “We truly created a village atmosphere at Wardell this summer and we all felt greatly honored to be given the chance to excavate at such an important site.” It also appears that much of that joy evolves from an admiration and respect for the career contributions of Dr. George Frison who led the original dig in 1970-1971.

Dr. Frison used the Wardell site, as well as many others throughout the high plains, to revolutionize the theories on Paleo-Indian and the understanding of hunting culture. His book, “Prehistoric Hunter of the High Plains,” is a must reference for any professional. Dr. Frison was honored as ‘Paleoarchaeologist of the Century’ at the 1999 Clovis and Beyond Conference, sponsored by the Center for the Study of the First Americans, and attended by 1400 people.

During Frison’s two field seasons, over three tons of bones, more than 400 projectile points, and some pottery were recovered. Most of these artifacts are still stored at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. The large volume of bone and artifacts led to a huge jump in knowledge of late prehistory occupation of the Green River Valley.

WARDELL DISPLAY AT THE GREEN RIVER VALLEY MUSEUM

Some Wardell artifacts from the original 1970 dig are on display at the Green River Valley Museum in Big Piney. The exhibit at the Museum includes a 4' by 8' mural of the site painted by artists Lynn Thomas, Charmian McLellan and Ruth Rawhouser, assisted by Ann Anspach, Tib Sutherland, Mary Krause and Betty Pfaff, who collaborated to create an artist's conception of history. The large mural fills the wall behind a display case of Wardell artifacts and gives a great representation of how the trap was likely used. The Museum is open during the summers.

FUTURE FOR THE WARDELL SITE

The current excavation is now complete, and stabilization efforts will hopefully be completed this fall. Crews will lay down erosion matting, soil and rip rap in the deep gullies and install small check dams to control further erosion.

The real work of analyzing the bone and artifacts has not even begun. Drucker estimates it will take four hours of lab work for every hour spent in the field. There is no funding for further research or plans on how to clean and study the bone artifacts. It is likely to be an all-volunteer effort which will include members of the Wyoming Archaeological Society (WAS) for future work. Many people have already offered their help. The BLM hopes to find funding for scientific testing for carbon-14 dating, obsidian identification, and other research.

According to Drucker, two people will do master thesis projects as a result of the dig. Anna Yoder will be working on Wardell Trap overview, taking into consideration how the trap was used in context with other nearby features, such as stone circle sites. David Crowley will be doing a lithic analysis specifically to compare stone tools to those known further north in Montana and Canada, to further explore the potential Athabascan connections.

Sam Drucker will give a presentation about the Wardell excavation at the upcoming Rocky Mountain Anthropological Conference in Park City, Utah, September 16-17, 2005. He will also be giving a special presentation for the Green River Valley Museum’s season-ending program on Wednesday, October 12th, at 7 pm at the museum in Big Piney.

Drucker hopes to update the Wardell site form with new information, and he will undoubtedly write many reports about Wardell in the years to come. Drucker is commited to cleaning and analyzing bones and artifacts from Wardell. For Sam, the project has just begun.

The location of the Wardell Buffalo Trap is not being publicized to minimize the chance of looting. The site is on Federal property and is protected by the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 and the Antiquities Act of 1906. Anyone not authorized found digging or collecting artifacts at the site, as well as anywhere else on Federal land, could face heavy fines and even prison time. The site will be regularly monitored.

Regardless of the law, please do not pickup and remove any cultural materials. Instead leave anything you find in place and report them to someone who can properly document them. The 28 arrowheads recently found at the Wardell site, given the context in which they were found, may help establish the tribal affiliation of the hunters, could lead to a better understanding of the peopling of the Green River Valley and even North America, and could increase our understanding of tool evolution. The same 28 arrowheads out of context in a frame on somebody’s wall would be meaningless.

References:

“The Wardell Buffalo Trap 48 SU 301: Communal Procurement in the Upper Green River Basin, Wyoming”, by George C. Frison, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan No. 48

“Prehistoric Hunters of the High Plains”, Edited by George C. Frison, Academic Press Inc. 2nd Edition, San Diego, 1991

|