Court sides against Robbins

by Cat Urbigkit

June 25, 2007

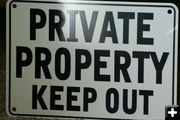

On Monday, the United States Supreme Court issued its decision in the Bureau of Land Management’s lawsuit against Harvey Frank Robbins, siding against Robbins.

Robbins had asserted that the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause forbids government action calculated to acquire private property coercively and cost-free. The Robbins case detailed an organized campaign of harassment and intimidation aimed at the rancher after he refused to grant the BLM a right-of-way. The high court decided not to allow the case under the constitutional claim, citing the fear of opening the floodgates for similar claims against federal agents.

The court decided Robbins had a no constitutional claim for remedy. It stated:

"We think accordingly that any damages remedy for actions by Government employees who push too hard for the Government’s benefit may come better, if at all, through egislation. “Congress is in a far better position than a court to evaluate the impact of a new species of litigation” against those who act on the public’s behalf. And Congress can tailor any remedy to the problem perceived, thus lessening the risk of raising a tide of suits threatening legitimate initiative on the part of the Government’s employees.”

“The point here is not to deny that Government employees sometimes overreach, for of course they do, and they may have done so here if all the allegations are true,” the court noted in its 7-2 decision.

The decision went through Robbins’ individual run-ins with the BLM and concluded, “when the incidents are examined one by one, Robbins’s situation does not call for creating a constitutional cause of action for want of other means of vindication.”

The majority decision held: “In sum, Robbins has an administrative, and ultimately a judicial, process for vindicating virtually all of his complaints. He suffered no charges of wrongdoing on his own part without an opportunity to defend himself (and, in the case of the criminal charges, to recoup the consequent expense, though a judge found his claim wanting). And final agency action, as in canceling permits, for example, was open to administrative and judicial review.”

The decision continued: “This state of the law gives Robbins no intuitively meritorious case for recognizing a new constitutional cause of action, but neither does it plainly answer no to the question whether he should have it. Like the combination of public and private land ownership around the ranch, the forums of defense and redress open to Robbins are a patchwork, an assemblage of state and federal, administrative and judicial benches applying regulations, statutes and common law rules.”

The court noted: “It is one thing to be threatened with the loss of grazing rights, or to be prosecuted, or to have one’s lodge broken into, but something else to be subjected to this in combination over a period of six years, by a series of public officials bent on making life difficult. Agency appeals, lawsuits, and criminal defense take money, and endless battling depletes the spirit along with the purse. The whole here is greater than the sum of its parts.”

The court continued: “On the other side of the ledger there is a difficulty in defining a workable cause of action. Robbins describes the wrong here as retaliation for standing on his right as a property owner to keep the Government out (by refusing a free replacement for the right-of-way it had lost), and the mention of retaliation brings with it a tailwind of support from our longstanding recognition that the Government may not retaliate for exercising First Amendment speech.”

“All agree that the Bureau’s employees intended to convince Robbins to grant an easement. But unlike punishing someone for speaking out against the Government, trying to induce someone to grant an easement for public use is a perfectly legitimate purpose: as a landowner, the Government may have, and in this instance does have, a valid interest in getting access to neighboring lands.”

Robbins has also filed a Racketing claim against the federal employees, but the high court shot that down as well, noting “the conduct alleged does not fit the traditional definition of extortion.”

|